Screenshot of PSCU's virtual panel with three credit union CEOs led by PSCU EVP and CFO Brian Caldarelli.

Screenshot of PSCU's virtual panel with three credit union CEOs led by PSCU EVP and CFO Brian Caldarelli.

One experimental aspect of adjusting to our new, physically-distanced way of life in the credit union industry has been participating in virtual conferences. I recently listened in on two that were adapted from cancelled in-person events to a virtual format: PSCU's Virtual Member Forum and NAFCU's State of the Industry. Organizers have done an excellent job of pivoting quickly to bring as much value as possible to attendees under new limitations, and they should be commended for their efforts. Of course, "attending" a conference virtually comes with pros and cons.

Pros: No traveling, which means no 6 a.m. flights, no overpriced room service, and no dragging my laptop around a convention center while searching for a power outlet to get some work done. And lots of hours back in my schedule, which means I'm always on top of emails and assignments.

Recommended For You

Cons: No traveling, which means no more feelings of exhilaration that come from visiting a new city, and no forging the types of connections that can only be made in person. No spontaneous, organic conversations in a hallway or at the hotel bar, which for me have often led to new working relationships and story ideas.

As much as we'd like to believe virtual conferences are filling the void left behind by the ghosts of bustling conferences and trade shows past, they just aren't. Nevertheless, I've found them to be a good way to hear first-hand what people out in credit union land have been experiencing since the pandemic turned our lives upside down. Here's what three CEOs had to say while being live-streamed from their offices during PSCU's virtual event.

California Coast Credit Union ($3 billion, San Diego) CEO Todd Lane

Lane opened the virtual panel by commenting on a well-known current point of contention across the U.S. – differing levels of compliance with social distancing guidelines among different groups of people. Lane's credit union operates in California's San Diego and Riverside counties, and he noted while members in one county appeared to be making decisions to help control the spread of the virus, members in the other had become less strict about distancing and were not happy about some of the newly-implemented safety measures at branches.

With the virtual event taking place as protests against racism and police brutality swept the country, Lane also revealed that on May 30, rioters destroyed a California Coast branch in La Mesa as well as surrounding businesses with rocks, crow bars and baseball bats. However, he said many people in the community immediately stepped in to help with the recovery process. "It was the beginning of the healing in that community, but a lot more healing is necessary, and [the credit union's] role is to be a part of that," he said.

California Coast worked with health experts to redesign the layout of its branches, and Lane said the credit union saw a 40% decrease in branch traffic at one point while digital banking surged exponentially. As more members banked from home, Lane said the branch's role in sales and membership growth became evident. With members hurrying in and out of branches and employees refraining from making their usual sales pitches, new member and account growth began to drop, he admitted. The credit union is now exploring ways to build business remotely.

And like at many credit unions, California Coast's back-office and call center staff have been working from home. "I don't see that [onsite work] returning," Lane said. "We'll migrate some back-office employees back in, but 30% or more will continue to work remotely."

Border Federal Credit Union ($163.7 million, Del Rio, Texas) CEO Maria Martinez

Martinez didn't sugar coat the difficulties the pandemic has brought. "As leaders, we have it really tough right now. This has been the worst few months of my life as a leader," she admitted. "There have been a lot of sad days as I've wondered how we will make staff feel comfortable coming back to work."

BFCU is a low-income designated credit union and Community Development Financial Institution serving a rural, largely Hispanic community living near the Mexico border. Branch lobbies have been open by appointment only, and members who previously shied away from digital banking are now using it and seeing that it works, Martinez said. She added that the major shift to digital has raised concerns about the survival of small credit unions given the expense of implementing the technology.

Staff has also been working remotely – something BFCU wasn't prepared for. Staff members received new laptops, which Martinez said she plans to maximize the use of by allowing staff to bring them out into the field to open new member accounts for people who don't have access to transportation.

Despite the pain of physical distancing, Martinez has helped keep employees' spirits up by hosting a weekly Zoom meeting, where they play games and find other creative ways to connect.

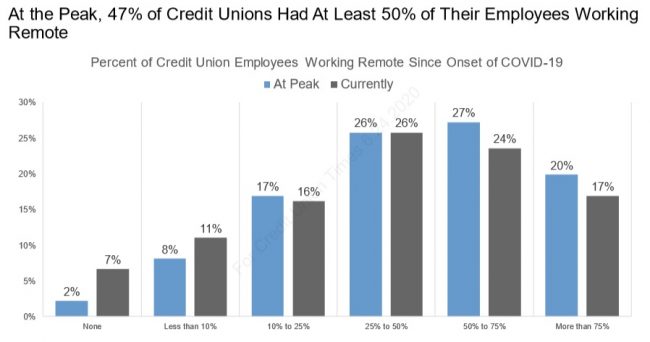

Remote work has become a key area of focus for CUs amid the pandemic. Source: Raddon COVID-19 Institution Survey, May 2020

Remote work has become a key area of focus for CUs amid the pandemic. Source: Raddon COVID-19 Institution Survey, May 2020 Note: The average asset size of responding credit unions was $1.46 billion; the median asset size of responding credit unions was $848 million. Ninety percent of the surveys were completed between May 15 and 22.

BCU ($4 billion, Vernon Hills, Ill.) CEO Mike Valentine

BCU shut down all of its branches, half of which are located inside SEGs' offices, for 10 weeks and began reopening them for appointments in early June. Valentine said branches are still important for building business and financial counseling, but that the pandemic has also made the digital channel more critical. "We've been more productive in the technology area than ever because there's been a sense of urgency," he said. "It became really clear that we had to put the member first."

Valentine said BCU recently signed a lease on a 75,000-square-foot building that will allow employees to be well-spaced out when they return to work, but he agreed with Lane in that the prevalence of remote work is here to stay. He predicted in one year, 30% of BCU's staff will be fully remote, and 50% will maintain a hybrid of onsite and remote work.

The shift to remote work hasn't come without challenges, however. "I'm a people person, so I feel like a caged tiger at home," he admitted. "I set up between six and seven calls per day to catch up with others."

How long will it be before we gather again at credit union conferences and offices, and will it ever be the same as it was four months ago? No one knows. For now, we have to work with what we've got and take comfort in hearing about the challenges other professionals are facing, even if it's through a screen.

Natasha Chilingerian

Natasha Chilingerian Natasha Chilingerian is executive editor for CU Times. She can be reached at [email protected].

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.