Source: Shutterstock

Source: Shutterstock

Capital is the lifeblood of a credit union, providing a cushion for anticipated and unidentified losses, a base for future growth and a means to meet competitive pressures as they arise. As a general rule, the greater the uncertainty a credit union faces, the more capital it should maintain. A strong capital position provides a credit union additional flexibility to manage risk and respond to future uncertainties such as asset losses, sponsor layoffs and adverse economic cycles.

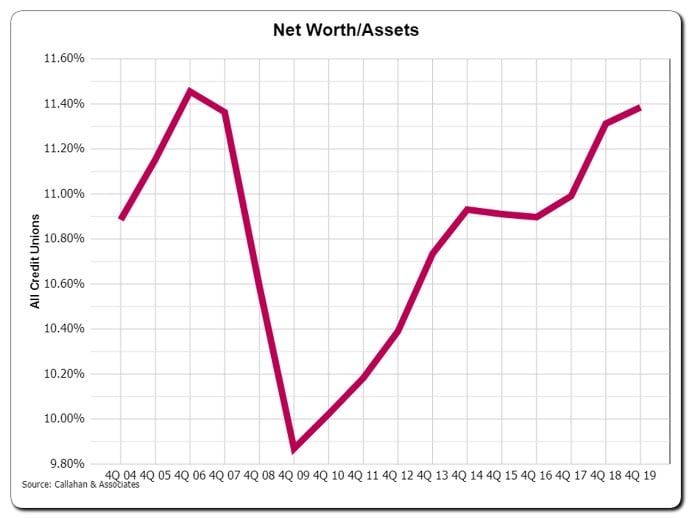

The most basic test of a credit union's capitalization is the net worth ratio, which measures an institution's retained earnings as a percentage of its total assets. As the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, credit unions found themselves very well capitalized. At 11.38%, the nation's 5,349 credit unions ended 2019 with one of the industry's highest average net worth ratios ever recorded, having added more than 150 bps to the ratio since the 2009 trough (9.87%).

The challenges in response to the coronavirus episode, however, are likely to be as difficult as credit unions have confronted. And, as they navigate unprecedented effects on provisions for loan and lease losses in the short-to-medium term, credit unions would be wise to examine the ongoing pressures that are likely to be brought on their capital stock. The balance of this article highlights three specific headwinds to capital that credit unions are likely to confront in the months and years ahead.

The first headwind on capital stems from the potential for increased deposit inflows in the shorter term – a typical response to periods of market volatility. These flows can threaten net worth ratios by ballooning the ratio's denominator, total assets, before the money can be put to an efficient use. The second challenge – the extension of additional credit and the loan forgiveness encouraged by the regulators in response to the pandemic – is likely to compromise credit union earnings over time. Finally, the third potential drain on capital can be found in the existing unfunded commitments of credit unions, as struggling members are more likely to draw on these lines in uncertain times.

Together, all three of these possibilities speak to the need to consider an additional capital cushion.

Deposit Inflows Can Stress Capital Ratios

In recent days, deposits have poured into the largest U.S. banks, as consumers and corporate clients seek shelter from the economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic. For example, deposits at domestically chartered commercial banks rose by a dramatic 42.5% in March, according to Federal Reserve data. While the intra-quarter credit union data are more difficult to come by, there is no reason to believe their experience is dissimilar. Anecdotally, our clients have certainly reported a pickup in member deposits coming in the door and expect more significant inflows as the Economic Impact Payments are credited.

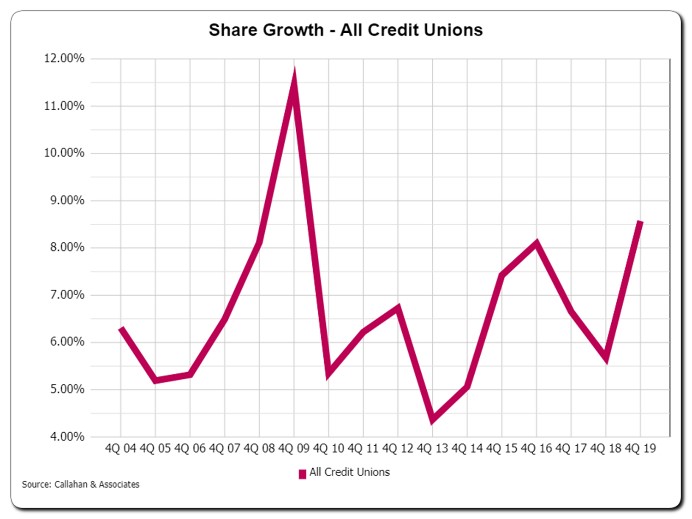

It is not uncommon to see a flight to quality in response to the type of market upheaval we have witnessed over the past two months. In a whirlwind, the federal insurance on deposits up to $250,000, available at both banks and credit unions, offers a certain stability. Credit unions have witnessed this trend before. For example, as the financial crisis took hold a decade ago, the industry was deluged with share growth at unprecedented levels, as members consolidated investments. Industrywide, the fund inflows resulted in asset growth outpacing the ability to grow net worth, driving the industry's average net worth ratio down 1.49% to 9.87% by in the two years ending in 2009.

Source: Callahan & Associates

Source: Callahan & Associates Source: Callahan & Associates

Source: Callahan & AssociatesThe Regulatory Response to COVID-19 Can Stress Capital Cushions

Three days after President Trump declared the coronavirus pandemic a national emergency, NCUA Chairman Rodney Hood responded with a letter to credit unions observing that "[a] credit union's efforts to work with members in communities under stress may contribute to the strength and recovery of these communities." The NCUA encouraged specific member accommodations, including fee waivers, the easing of credit terms, increased borrowing limits and loan modifications to ease pressure on borrowers.

These emergency measures are designed to help people avoid potential economic catastrophe and make good long-term business sense, and are in keeping with the credit union spirit of "people helping people."

The Federal Reserve echoed these sentiments on April 1, noting that "financial institutions have more than doubled their capital and liquidity levels over the past decade and are encouraged to use that strength to support households and businesses." But, the accommodations the regulators seek will present significant challenges to both liquidity and capital.

Writing new loans during emergency circumstances – where the normal operations of the credit union have been interrupted, the typical borrower is in distress and the regulator is encouraging the extension of credit – does not suggest the most prudent underwriting standards. And, maintaining the appropriate level of liquidity with atypical deposit flows and unnatural loan demand will challenge even the most well-run credit unions. Regardless, the combination of processing emergency loans and modifying existing loans will put pressure on credit union earnings with the passage of time.

Thankfully, credit unions are in a desirable place from which to defend these mounting challenges, with profitability near all-time highs. Return on Assets, for example, has been creeping up steadily in the industry since 2009, with the 0.93% at year-end 2019 just a touch lower than the decade's high reached in the quarter earlier. Net interest margin has also been increasing since 2013.

Unfunded Commitments

In this environment, credit unions should also keep an eye on unfunded commitments as a percentage of total assets. The thought here is that distressed members might be more likely to pull down on committed lines in these uncertain times. Such actions could strain the liquidity (and ultimately the capital) of a credit union. Looking at all credit unions, in 2019 the average unfunded commitment to total assets ratio is a modest 17%. There are, however, 24 credit unions with unfunded commitments representing more than 40% of assets, 57 credit unions with unfunded commitments representing more than 33% of assets and 201 credit unions with unfunded commitments representing more than 25% of assets, respectively.

Secondary Capital

If the coronavirus pandemic and the related responses result in the depletion of capital that historical norms suggest, additional sources of capital will be in high demand. Such additional capital affords credit unions the flexibility to dispense the appropriate accommodations for members displaced by this event while maintaining safety and soundness. The NCUA's recent subordinated debt proposal, if it comes on board, should help those deemed "complex credit unions." Fortunately, low-income designated credit unions do not have to wait so long, as there is a solution already available today.

Since 1996, low-income credit unions (LICUs) have been permitted to accept secondary capital. Secondary capital provides a boost to net worth and opens options to expand loan portfolios, assets and services, allowing LICUs to stimulate the economies of the low-income communities in which they operate.

As of Dec. 31, 2019, more than 48.9% of all credit unions held a low-income designation. Yet, only 68 LICUs employed secondary capital. With all the uncertainty and the desire to assist members reeling from the pandemic and its fallout, we expect this number to grow steadily. In the age of COVID-19, additional capital sounds like an awfully good idea.

Mike Macchiarola

Mike MacchiarolaMichael Macchiarola is CEO of Olden Lane, a financial services firm based in Chatham, N.J.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.