Headline in The New York Times the day after President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Federal Credit Union Act in June 1934.

Headline in The New York Times the day after President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Federal Credit Union Act in June 1934.

When a Winston-Salem, N.C., credit union extended membership to workers at a small furniture company located down the road, it set off a battle with bankers that threatened the future of the movement.

Americans' access to credit unions has expanded dramatically over the past 20 years. In no small part, the growth came because of credit unions' ability to counter a battle that bankers launched in 1990 against that credit union, then known as AT&T Family Federal Credit Union, which had $223.7 million in assets and 66,895 members.

Today, that credit union is known as Truliant Federal Credit Union, which had $2.6 billion in assets and 245,849 members from southwest Virginia to northwest South Carolina.

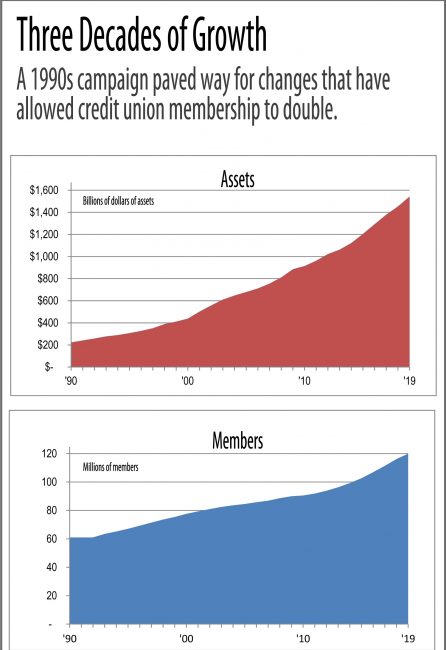

Meanwhile, the credit union movement as a whole has doubled from 61 million members in 1990 to more than 120 million in June.

"We're now at about a third of the U.S. population, and that's a pretty good distance to have traveled," Marc Schaefer, who spent most of his career leading Truliant, said.

Schaefer will retire at year's end as CEO as the board hands that title to Todd Hall, who took over from Schaefer as president this summer.

As someone who has participated in the movement that has allowed his and other credit unions to thrive, Schaefer said credit unions must work even harder in the coming years.

"There's always going to be challenges. The banking industry is always going to try not only to limit us, but to eliminate us," he said. "My hope is we will continue to be able to differentiate ourselves from the banking industry – through our actions, how we treat consumers, how we serve middle and lower-income Americans, and continue to be able to have a compelling value proposition."

In 1990, bankers sued AT&T Family, saying allowing the new members under a 1982 NCUA regulation violated the original law signed by President Franklin Roosevelt in June 1934. The credit union won the first round in September 1994 when the federal district court in Washington, D.C., ruled in its favor. But the bankers appealed.

Meanwhile, in January 1995, the credit union hired a new president/CEO who had experience with bankers from an unusual perspective. Schaefer had been president/CEO of FDIC Federal Credit Union. It might seem odd that banking regulators were credit union members, but the arrangement helped prevent the regulators from having to police banks that might be keeping their money or providing them loans.

Schaefer began his credit union career with U.S. Postal Service Federal Credit Union in 1982 after he received his MBA from the Thunderbird School of Global Management in Phoenix, Ariz. In 1986 he was hired as president/CEO of FDIC FCU, which through mergers will soon be part of NASA Federal Credit Union.

The case got standing in the U.S. District Court of Appeals in January 1996 – a signal that the court felt the bankers had a strong argument. After the appeals court ruled in the banks' favor in July, Schaefer and others in the credit union movement launched the "National Credit Union Campaign for Consumer Choice."

A grassroots campaign was a bold move for a movement with a reputation for being as noisy as a herd of librarians. But the credit unions had members in every House member's district, and they mobilized their members and trade organizations to persuade Congress to change the law, so they would be able to more easily merge and serve communities that were broader than their original, strict employer ties. "We got busy," Schaefer said.

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in the banks' favor in February 1998 based on the old law, the credit unions had made their own case for a new law.

The credit unions' strength was shown by the fact that the bill that would undo the Supreme Court ruling already had 138 co-sponsors from both parties, including House Speaker Newt Gingrich. And Senator Alfonse M. D'Amato, the New York Republican who was then chair of the Senate Banking Committee, had signaled support for such a bill.

"This is a major, massive survival issue for us and we plan to win," Dan A. Mica, then president of CUNA, said.

Headline from The New York Times after the U.S. House passed the Credit Union Membership Access Act in April 1998.

Headline from The New York Times after the U.S. House passed the Credit Union Membership Access Act in April 1998.The Credit Union Consumer Access Act, which loosened credit union membership restrictions, passed the House in April 1998 by a vote of 411-8, the Senate in July and was signed into law by President Clinton in August.

"Congress saw that consumers needed a choice; they needed access," Schaefer said. "That was a pretty significant milestone in the ability of credit unions to serve consumers."

From 1998 to 2008, the first full year of the Great Recession, credit union assets more than doubled to $811 billion, while members rose 20% to 89 million. From 2008 to the end of 2018, assets grew 79% and members grew 31%.

As of June, credit unions had $1.5 trillion in assets and 120 million members – marks that CUNA had forecast would be reached by year's end. But Schaefer and other credit union leaders warned that boards and managers need to remain vigilant to threats to their ability to serve more Americans.

Source: The NCUA

Source: The NCUA"The culture is the franchise," Schaefer said. "If you can't carry that culture forward, you're not going to be successful long term."

One argument floated by the American Bankers Association is that credit unions can be good – if they are small.

"That's totally disingenuous," Schaefer said. "The banking industry's goal is to separate large from small, and to try to make the argument that large credit unions are banks. It's just not true. If you really want a viable credit union option in the United States, you have to have credit unions of size that have the wherewithal to provide what consumers want."

That means credit unions need to be investing heavily in technology to be providing the level of services that consumers expect when they walk in the door, or work with their account online. That means having systems that allow quick online loan applications, ATM networks that allow ready access to cash and mobile apps that allow members to deposit checks remotely when they don't have time to drop by a branch.

"Having a little credit union in the basement will not do that," Schaefer said. "But that's what the banking industry wants. That's what they wanted back in 1990 when they sued us."

During the Great Recession, U.S. taxpayers spent $498 billion bailing out banks, an amount equal to 3.5% of the nation's 2009 gross domestic product, according to an MIT study released this year using a fair-value analysis.

As banks cut back on lending during the recession, credit unions were largely able to keep credit flowing to members and pick up new ones set adrift by banks.

Banks' relationship with consumers has been further tainted by practices that led to fines by regulators. For example, Wells Fargo has paid more than $15 billion in settlements since the financial crisis to resolve investigations into misdeeds.

"The banking industry has proven our point with the financial crisis and some of the things with some of the large banks," Schaefer said. "You need a viable financial services sector with credit unions that are relevant and of a size so that consumers have an option."

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.