Strategy drives the focus of a successful PMO.

Strategy drives the focus of a successful PMO.

A sampling of over 20 credit union leaders at last year's NAFCU Management and Leadership Institute revealed a common problem across the industry. That problem is successful project execution. This is not a problem unique to the financial industry, as last year, the Project Management Institute reported 24% of projects were deemed failures for under-performing and at best, 6% for high-performing organizations.

A common approach for improving project success is forming a Project Management Office to help guide project completion. At NAFCU's MLI, one credit union using this approach reported nearly a 200% increase in project completion, while another did not see a significant improvement. What set the two experiences apart and how does a credit union determine if a PMO is right for their organization?

Recommended For You

Before a credit union leader decides to form a PMO, there are some very pragmatic questions that need to be answered. The first is whether the credit union is executing enough projects, and at a rate to warrant a PMO. A clear sign of this need is if projects are conflicting with each other by consuming the other's resources. The next question is if the credit union is large enough to support a PMO. A PMO can be ran with as little as a 0.5 FTE and scale up depending on the complexity of the organization and project focus.

For a PMO to be successful in delivering organizational value, it must be aligned with strategy. The PMO is the execution arm of strategy, which involves ensuring projects are committed, resourced and managed. This takes organizational maturity for a credit union to develop a strategy with a vision to support it. Ideally, the strategy will be decomposed into initiatives that define work that is both actionable and finite in time – projects usually represent that work.

Using the classic strategy model of ends, ways and means, ends are what leaders desire at the end state, initiatives are the ways and projects are often means. The PMO helps ensure those projects, or means, are completed, which supports initiatives, or ways. Together, they deliver what is strategically needed, or ends. If a PMO is not executing strategy, the value of that PMO will be low and project teams will often move agendas that are not supportive of needed end states.

PMO offers its highest value when the credit union organizes strategy in portfolios and programs, which conveniently enough maps directly to ways. Frequently, leaders in organizations will say a project is ongoing, which contradicts the PMI's definition of a project. Paraphrased, that definition, reminds leaders that a project is a temporary undertaking for a specific outcome. Projects cannot be ongoing, but programs or initiatives can be enduring.

There are several steps in forming a PMO. The first is a candid assessment of the political atmosphere in the credit union. Forming a PMO will likely be a departure for the cultural norms and because of that, it is important to understand what norms might be effected, like perceived power and influence shifting in the organization. Secondly, it is important to charter the PMO, which sets expectations of exactly what the PMO does and does not do for the organization. Having those expectations set will alleviate a lot of concerns. Further, a charter can be tailored to address those issues identified in the political assessment.

Figure 1: Establishing your credit union's baseline project theoretical throughput

Figure 1: Establishing your credit union's baseline project theoretical throughput When considering the staffing level of a PMO, a credit union leader should baseline their organization first. This is done with some basic project metrics and straight-forward math. First, get the number of actual projects completed the year prior, call this variable A. Then determine the average project duration and call that variable B. Next, determine the number of project managers in the organization, even if they are in an unofficial capacity, call this variable C. Divide A by C to get average project manager load, and call this D. Pulling this all together to get the theoretical throughput, the formula reads (12/B) x (C x D), where 12 is the number of months in a year. Figure 1 illustrates this equation and shows that this credit union is underperforming on the theoretical project throughput.

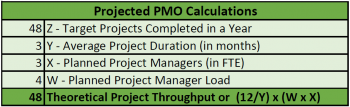

Figure 2: Calculating your credit union's target theoretical project throughput

Figure 2: Calculating your credit union's target theoretical project throughput Next is right-sizing the PMO staff, which is similar math. Variable Z represents the target number of projects the management would like for the PMO to accomplish in the next year, 150% of A is a fair estimate to start. Then take B and multiply it by 0.6 for a projected 40% efficiency gain to get variable Y. Assuming full-time project managers can take a project load between three and five projects depending on complexity, take the average of four for variable W. Last is determining the right number of project managers in variable X, and this can take some trial and error, until the theoretical project throughput equals or exceeds variable A, as seen in Figure 2.

In performing these calculations, there are probably a few things that stand out. First, why is the theoretical project throughput of the PMO so much higher than the actual project completed the year prior in the baseline? This generally comes from waste, as a partial project manager who has a "day job" rarely has the project throughput of a full-time project manager. This is seen in the reduction of project duration as well. Second, the term theoretical suggests these numbers are guidelines, as every credit union will be different and some may perform better or worse depending on their organizational environment.

A question that often comes up when considering forming a PMO is: Who should lead the PMO? There is a good argument for promoting within, if the political environment is amenable to the discipline a PMO would introduce. However, if the organization is ambivalent and the cultural friction is a factor, an external hire would likely do best. An experienced external hire can often negotiate the politics with a committed focus on executing the organization's strategy through projects, which might be the right choice for some credit unions.

Forming a PMO is an undertaking that needs to be well reasoned and planned. Before a credit union leader forms a PMO, it is necessary to peform the due diligence to ensure that the organization has the need and is mature enough to support a PMO. Strategy is what drives the focus of a PMO if it is to return the greatest value as it marshals resources to achieve the strategic end state. A well-executed PMO can deliver tantalizing results, and dramatically push project success to levels that are unachievable when left to independent efforts.

Ray Ragan

Ray Ragan Ray K. Ragan, MAd (PM), PMP is Assistant Vice President of Project Management for Vantage West Credit Union. He can be reached at 520-617-4014 or [email protected].

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.