For decades, the U.S. system of higher education has operated on a unique premise: To make college affordable for a broad swathe of Americans, student debt must be an almost inviolable obligation.

For decades, the U.S. system of higher education has operated on a unique premise: To make college affordable for a broad swathe of Americans, student debt must be an almost inviolable obligation.

Now, authorities are starting to question that assumption. It's about time.

Capitalist societies have long taken a forgiving approach to people who can't pay their debts. The rationale is that allowing them to seek relief through bankruptcy makes everyone better off: Creditors get what they can, the individual gets a second chance, and society benefits from a legal system that encourages people to take risks.

Recommended For You

Student debt is a rare exception. In the 1970s, spurred by stories of college graduates reneging on federal loans, Congress granted it special status. Unlike other obligations, such as credit-card balances, it can't be discharged in bankruptcy unless it imposes an "undue hardship." Courts narrowed that escape route further, in some cases demanding that borrowers demonstrate a "certainty of hopelessness" — an almost impossible standard to meet. As a result, debtors almost never seek relief.

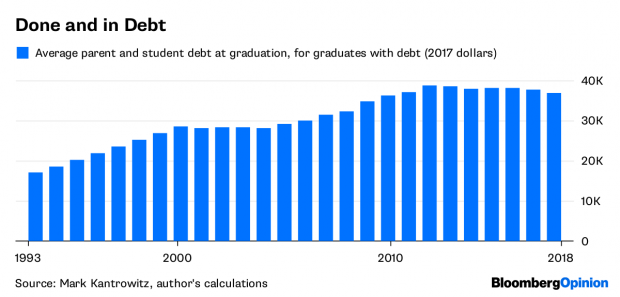

Those precedents, though, were set at a time when student debt wasn't the big deal it is today. As federal aid — which once covered as much as 77% of a public-university degree — has failed to keep pace with expenses, educational debt has surpassed auto and credit-card debt to become U.S. households' second-largest obligation after mortgages. Financial-aid expert Mark Kantrowitz estimates that in 2018, students and parents who took on debt owed an average of $36,888 at graduation. That's down from recent years in inflation-adjusted terms, but more than double the level of 1993.

The burden has fallen particularly heavily on the poor, who have all too often invested in education only to find themselves unable to complete a degree or cheated by for-profit institutions. As of 2016, the latest data available from the Federal Reserve, average education debt for the poorest fifth of U.S. families amounted to almost a third of annual income, up from less than a tenth in 2001. That compares with just 3% for the wealthiest fifth of families.

Those who can't pay are relegated to a modern-day form of debtors' prison. Interest keeps accruing, so balances can balloon many times over. Even borrowers fortunate enough to qualify for federal income-based repayment plans, which cancel remaining debts after 20 to 25 years, face a tax bill for the forgiveness. The nearly 5 million people who have defaulted suffer a ruined credit record, which can affect everything from their job prospects to their chances at homeownership. Inevitably, the economy suffers.

This is precisely the situation that bankruptcy was designed to address — a fact that authorities ranging from prominent academics to Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell have publicly recognized. Now, judges are taking matters into their own hands. Across the country, they are increasingly ruling in favor of discharging student debt, writing opinions aimed at changing the interpretation of "undue hardship."

To provide more clarity, it would be better if Congress passed a law repealing the anomalous status of student debt. Granted, treating those obligations like most other debt could make lenders — private and public alike — think more carefully about extending loans in the first place. But that might be no bad thing. In any case, as long as Congress remains reluctant to act, judges are right to do what they can through legal precedent. The Department of Education could help as well, by heeding the advice of legal experts and easing its historically aggressive approach to opposing discharges.

The U.S. needs a better way to make higher education broadly accessible — in the first instance, by developing a simpler, broader and more sustainable income-based system for recovering costs. For now, though, the existing debts loom large.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.