Two credit unions carrying up to a 45% concentration of home equity lines of credit said the loans are not at risk or that they have taken steps to monitor and mitigate potential risk.

Federal and state regulators drew attention to the issue when they issued guidance about it in July.

TransUnion then reported Aug. 7 that HELOCs transitioning from draw to repayment could default.

HELOCs opened from 2005-2008, during the years leading to the financial crisis, were most at risk, TransUnion reported.

These HELOCs typically had a 10-year draw period, during which time the borrower could use funds up to his or her limit.

Following that 10 years was a 15- or 20-year pay-down period when the borrower must pay back the line of credit line's amortized principal and interest.

During the draw period, consumers generally make interest-only payments, TransUnion said.

According to the Chicago-based firm's data, $438 billion in HELOCs had not yet reached the end of their draw period and entered their pay-down period as of the end of December 2013.

These borrowers are potentially susceptible to payment shock, the firm said, since many of them may not be prepared for the sometimes 60% increase in payment amounts once the pay-down period starts.

“Home equity lines of credit were quite popular during the housing boom in the mid-2000s,” Steve Chaouki, head of financial services at TransUnion, said. “For many people, HELOCs represented a low-interest rate opportunity to borrow against the value of their homes, which were rapidly appreciating at the time. HELOCs generally had lower interest rates than credit cards or other loan types, and that interest was often tax-deductible.”

TransUnion's research found lenders originated nearly half of all HELOC balances between 2005-2007.

Many of these HELOCs had 10-year draw periods, and for those borrowers the draw period will come to an end over the next few years, TransUnion said.

“Some HELOC borrowers may not find this a problem,” explained Ezra Becker, vice president of research and co-author of the TransUnion study. “They may have the excess payment capacity to absorb the increase or they may have the equity in their homes to refinance the HELOC. But many borrowers won't have these and they are at risk.”

Becker said the risk was not only in the possibility borrowers may default on their HELOC, but also that borrowers may default on other loans in favor of making the HELOC payments.

“They may conclude that house prices are rising, I really want to protect my home, so I will pay the HELOC and let the credit card go,” he said.

However, TransUnion's research showed credit scores were still very a good predictors of how a borrower will perform during the pay-down period of a HELOC, particularly the enhanced scores that measure, for example, how many minimum payments a borrower makes on credit accounts versus how many payments he or she makes above the minimum.

And, Becker added, the challenge might also provide an opportunity.

A credit union might be well positioned to help a member refinance a HELOC about the enter the pay-down period from another lender, he noted.

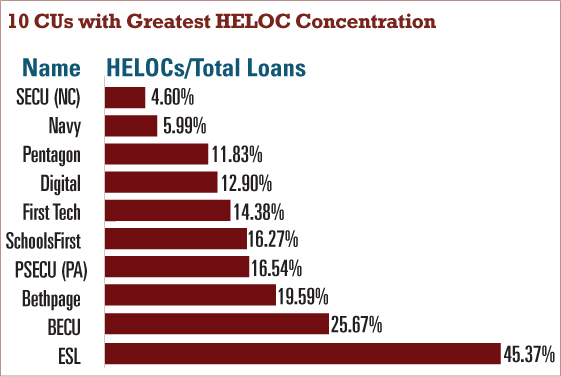

The $4.8 billion, 327,000-member ESL Federal Credit Union in Rochester, N.Y., had the largest concentration of HELOCs among federally insured credit unions, with 45.37% of its loan portfolio in the credit lines.

That translates into roughly $1.1 billion in home equity loans with about $900 million in HELOCs. ESL's credit lines have a 10-year draw and are paid down over 20 years, and their average balance is $35,000, the credit union said.

ESL FCU President/COO Faheem Masood predicted Rochester's long history of stable real estate prices would keep most ESL borrowers from slipping underwater on their homes and added that many would not face any sort of sticker shock when the pay-down period began.

“We have seen very little speculation in real estate in the Rochester market,” Masood said, adding housing prices had risen about 3% during the 2005-2008 run up to the housing crisis and then increased about 1% more from 2008 to 2010. Home prices have remained more or less the same, with small fluctuations either way, ever since.

“This is a very traditional housing market,” Masood added. “The overwhelming majority of real estate owners live in their property and we build equity in our homes by paying down our mortgages.”

That means if HELOC borrowers faced payments they could not or would rather not make in the pay down, they would almost certainly be able to refinance the loan with either the credit union or another lender, Masood explained.

In addition, the credit union has its borrowers pay back some of the principal even during the draw period, Masood said.

Each month, the credit union has the borrower pay the higher of either $100 or 17 basis points of the principal along with an interest payment.

Thus, the monthly payment on a HELOC with the credit union's best rate and an average balance of $35,000 would be roughly $156, he said.

That would increase to a little more than $200 during the pay-down period.

Todd Pietzsch, public relations manager for the $12.6 billion BECU, said the Seattle-based credit union had been aware of the potential risk for a couple of years and had already undertaken the problem.

The big credit union has roughly $1.9 billion in home equity loans with about 25% of its overall loan portfolio in HELOCs, according to data reported to the NCUA. BECU reported the average balances were about $39,000.

“We determined we had opened a lot of our HELOCs in the 2006-2007 period,” Pietzsch said, adding that since they have a 10-year draw, BECU was not going to start seeing members hit pay-down periods until 2016 and 2017. Before that time, Pietzsch said, the credit union expected home prices will have rebounded sufficiently to allow borrowers to refinance their debt.

He also observed that not all of the credit union's HELOCs were the same.

Borrowers who opened a line for a specific purpose, such as repairing a roof, could begin the pay down early and at a fixed rate if they knew they had completed drawing on the line.

“Once the borrower has finished their $30,000 roof repair or whatever and know they are done, they can begin paying down,” Pietzsch said, adding that borrowers have 15 years to repay the loan if they take that option.

These loans also cut the credit union's exposure to possibly risky loans, he added.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.