Industry experts say due diligence can help credit unions avoid losses like those suffered by the $620 million Alabama One Credit Union in Tuscaloosa, Ala., and the Small Business Administration, which were defrauded of more than $3 million by a businessman.

Danny Ray Butler allegedly engaged in a check-kiting scheme that led to a $1.275 million loss at Alabama One. He also allegedly defrauded the SBA of $1.76 million through a loan to build a grocery store, according to a 51-count indictment and statements made Oct. 4 by U.S. Attorney Joyce White and FBI Special Agent in Charge Richard D. Schwein Jr., in Birmingham, Ala.

Butler was likely able to get away with the alleged check kiting scheme because he was well known in the community and had probably built a level of trust with the financial institutions involved, said Kent Moon, president/CEO of Member Business Lending LLC, a West Jordan-based CUSO.

Butler was likely able to get away with the alleged check kiting scheme because he was well known in the community and had probably built a level of trust with the financial institutions involved, said Kent Moon, president/CEO of Member Business Lending LLC, a West Jordan-based CUSO.

Moon, who has nearly 40 years of experience in the small business lending sector, once served as district director of the SBA's Utah district and as a financial analyst and senior technical adviser for the agency's headquarters in Washington.

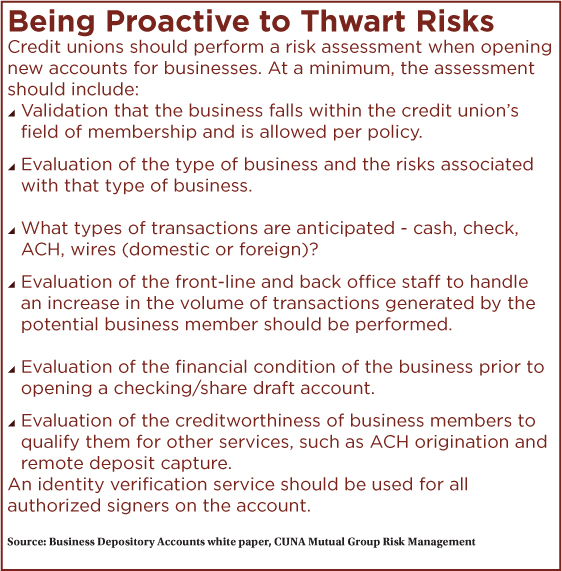

(Click on image at left to expand.)

During that time, he said he worked closely with the Department of Justice and the FBI in assisting with the prosecution of thousands of embezzlement and check kiting cases.

“The thing I learned is the people who are involved are typically normal, everyday people,” Moon said. “They're not going to come across as the criminal type or the Hollywood version of what that is. Usually, the chief suspects have built a high trust capacity in the community.”

For credit unions and other financial institutions, check kiting fraud is estimated to run into the billions of dollars in losses each year, according to some industry data. Even though check use is declining, the U.S. Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network found that check fraud has become the second most common crime reported in suspicious activity reports behind money laundering. Of the more than 50,000 SARs filed by depository institutions in 2010, the latest year tracked by FinCEN, the average suspicious activity amount was $766,270 and the average loss amount was $18,836.

With small businesses, check kiting typically occurs when the owner is experiencing a personal crisis such as a divorce or a death in the family, Moon said. The irony is the perpetrator doesn't think he or she is actually stealing, he explained. Instead, the business owner believes he or she is borrowing the money, and has every intention of paying it back.

“It's hard to protect yourself from someone you trust,” Moon said. “This happens more frequently than people realize. I'm always amazed at how many businesses and financial institutions get nailed.”

For credit unions, check kiting protection goes back to the basics, Moon noted. There must be strong procedures in place for cash verification. When surprise verifications occur, the business owner doesn't know when the accounts will be checked, which gives the financial institutions more time to follow the trail, he said.

Other red flags credit unions need to watch for are deposits of increasing dollar amounts and frequent returns of unpaid checks, said Ken Otsuka, senior consultant, risk management at CUNA Mutual Group in Madison, Wis.

Over the years, Otsuka said he has seen new account fraud cases where the culprit pretends to be a business owner, opens an account at a credit union, starts making deposits and then withdrawals the funds. There have also been cases involving dishonest employees who open an account in the name of the business without the authority to do so, Otsuka noted. The employee can then embezzle those funds from the business.

“Luckily, we don't see many of these cases,” Otsuka said. “When it does happen, the losses can be very severe.”

Next Page: Specific Written Policies

Otsuka said he is a firm believer in business members qualifying for certain products such as remote deposit capture and ACH origination. Written policies should specify the type of businesses a credit union wishes to attract and identify undesirable businesses, he suggested. Due diligence should always include evaluating a business's financial condition and requesting updated financial statements and tax returns on an annual basis to help detect any negative changes in a business member's life.

In their efforts to attract more businesses, some credit unions are offering RDC. Unfortunately, the remote service can help a business member maintain his or her check kiting scheme, especially if a credit union employee doesn't review the check image, Otsuka said. By qualifying members for RDC based on their financial condition and requiring annual checkups of financials, credit unions can spot any downward trends.

“We are seeing a trend with credit unions wanting to expand their fields of membership to attract business accounts or increase their service offerings to existing business members,” Otsuka said. “Regardless of where credit unions are at, an important starting point is having a policy that addresses businesses they want to avoid.”

For instance, while Otsuka doesn't want to suggest businesses such as check cashing stores increase risk, they have a tendency to attract fraudsters who might use them to launder stolen money, he said.

When it comes to check kiting, frontline staff may find it difficult to track suspicious activity because a business could be depositing high volume of checks and tellers may not have the time to check through all of them, Otsuka said. In these cases, tellers can look at the drawer's signature on the face of the check to determine if it belongs to the business member or an authorized signer.

In 2010, Butler contacted West Alabama Bank and Trust for a $5 million loan to build a grocery store, according to the indictment. He received bank approval for half the amount of the loan with the SBA agreeing to finance 35% of the project and Butler providing the remaining 15%. However, after construction was completed, Butler defaulted on the bank and SBA loan. It was discovered that Butler submitted false, forged and altered documents to get the SBA loan, according to the indictment.

In 2011 and 2012, Butler was allegedly involved in a check-kiting scheme that carefully timed deposits and checks between his grocery store account at West Alabama Bank and Trust and his Butler Wholesale account at Alabama One to artificially inflate the account balances, the indictment read. Checks totaling approximately $45 million were deposited from one account to the other at the two financial institutions.

Alabama One and the SBA did not respond to requests for comment.

According to the indictment, Butler was also allegedly involved in another scheme involving securing loans from NextGear Capital, a Carmel, Ind.-based financing company, to buy used vehicles for his car lot. He allegedly represented cars that were part of the dealership's inventory even though the cars were already sold.

Moon said based on what he read about the details in Butler's case, he secured a 504 loan from the SBA and needed to come up with $750,000 in cash. He started at a bank, then went over to the credit union and floated cash to give the appearance of liquidity.

“Any time you have a borrower using money to build a building and he's working with another financial institution, there should be verification of those balances with the other financial institution,” Moon said.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.