We compensate board members more out of a sense of fairness than anything else,” explained Lin Hodges, president/CEO of Associated Credit Union of Norcross, Ga.

“I just don't think we should use the argument that people should serve on a volunteer board because we have a higher calling. I just don't think that recognizes today's busy world and the way our financial institutions have changed. It has become dramatically more difficult,” Hodges added.

Only a small percentage of credit unions pay directors in states where board compensation is permitted to pay directors. What's more, most credit unions pay small stipends that range from a few hundred dollars or about $1,000 to $7,000 a year. However, in at least one instance, that pay exceeds $90,000 a year.

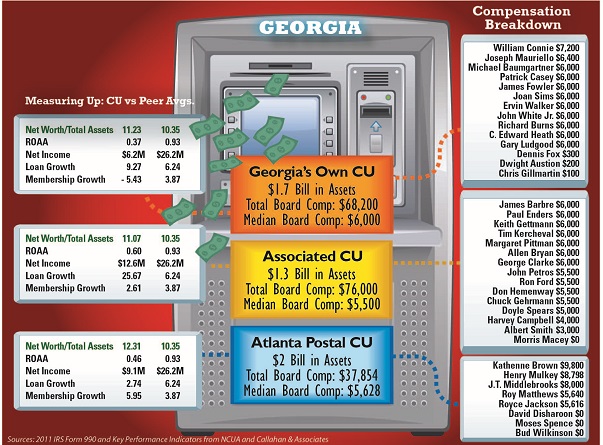

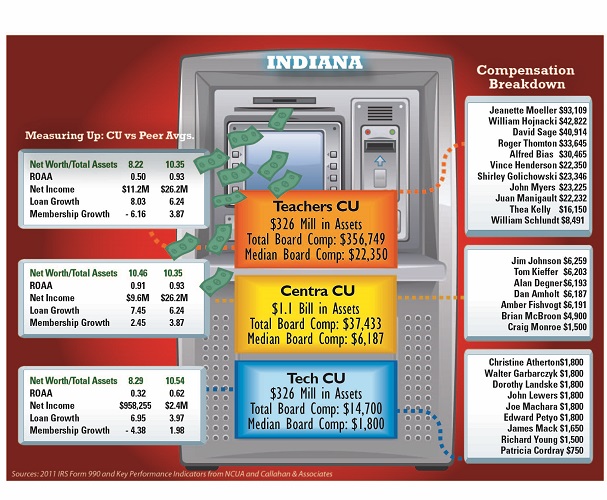

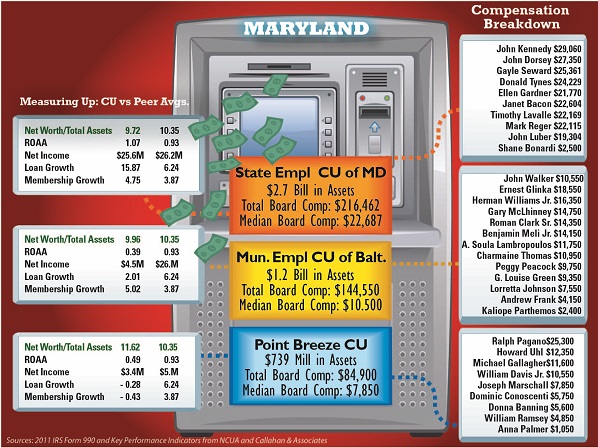

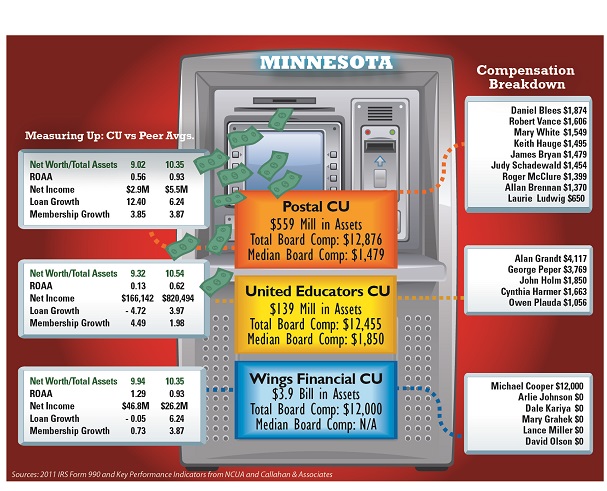

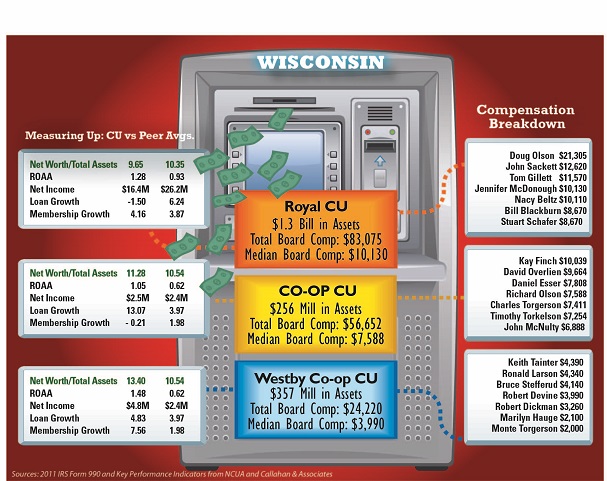

For this article, Credit Union Times compiled charts that list three of the largest state-chartered credit unions from each state that pay their board members. The charts also review how these credit unions performed financially in 2012 compared to their peers to see if they tended to perform any better, any worse or about the same as credit unions in their peer group, the vast majority of which do not pay their board members.

Credit Union Times reviewed more than 250 IRS Form 990 documents filed by state-chartered credit unions in 2011. To maintain their tax-exempt status, federal law requires state-chartered credit unions to submit an IRS Form 990 annually to report financial and operational information, including compensation of directors and executives. The IRS Form 990s revealed that many credit unions are paying their board members sizeable stipends for working one to five hours a week on board business, while a few others are working eight, nine or 10 hours a week.

More on Board Director Pay:

Part One – Surprised to Learn Volunteers Paid

Editorial – Time to Talk Turkey on 'Volunteer Boards'

Of the 26 CEOs at credit unions that pay board members contacted by Credit Union Times, eight agreed to an interview. The other CEOs either declined an interview or did not respond to our interview requests.

The CEOs interviewed said their boards are made up of professionals, such as small business owners, certified public accountants, lawyers, executives, real estate developers, insurance brokers and doctors who leverage their expertise and talents that keep the credit union financially sound and help it grow.

developers, insurance brokers and doctors who leverage their expertise and talents that keep the credit union financially sound and help it grow.

(CLICK on each of these graphics at the right and below to see expanded versions.)

The CEOs were asked three main questions: Why do they compensate board members? How do they determine what is reasonable compensation? And what value does the credit union get from paying board members?

Hodges, CEO of the $1.3 billion Associated Credit Union, said the challenges that credit unions face today require board members to spend more time and more work than ever on board business because of greater liability risks.

“In today's environment, the liability issue is more in your face, if you will, and regulators are quick to point that out,” Hodges said. Associated paid $76,000 in total compensation to its 15 board members in 2011, with a median annual stipend of $5,500.

Dave Root, president/CEO of the $229 million Coventry Credit Union in Coventry, R.I., agrees.

“I know there are some credit unions that are up in arms saying we might as well be banks if we compensate board members,” Root said. “But in this day and age, when you want to attract people who have some financial savvy, it's difficult to do that when you are asking people to volunteer their time, particularly when you have regulators who stare at board members in the face saying that they are subject to civil and monetary penalties if they don't do this or they don't do that.” Root said.

CU paid its 12 board members total compensation of $103,800 in 2011, with a median annual stipend of $8,400.

Gregory Smith of the $4.1 billion Pennsylvania State Employees Credit Union in Harrisburg said there is no question that boards are doing far more work than they did 10 years ago because the board's duties and responsibilities have become far more complex.

Smith said his board chair attends 10 to 12 meetings a month. He also said directors meet twice a month and go to committee meetings and special meetings that can number up to eight every month.

“It's a working board and it's not a job for the faint of heart,” Smith said. “It's not a cake type of job.”

Smith believes paying a PSECU board member a median annual stipend of $12,429 is reasonable compensation because they do “an awful lot of work.” The credit union, which paid nine board members total compensation of $122,622 in 2011, reports in its IRS 990 form that directors work eight to nine hours a week

But how do credit unions determine what is reasonable compensation?

IRS regulations require nonprofit organizations to compare what would ordinarily be paid to board members for similar services, duties and responsibilities among similar organizations in the region whether taxable or tax-exempt, according to Linda Lampkin, a Washington, D.C.-based research director for the ERI Economic Research Institute, a compensation and benefits research firm. Like circumstances account for the value of additional benefits such as insurance.

Every two years, the $2.3 billion Teachers Credit Union in South Bend, Ind., hires Mercer, a well-known HR consultancy to help determine what is reasonable compensation for directors and executives.

“It's something we make sure we get done by a well-regarded third party because [compensation] is a very delicate and sensitive topic,” said Teachers CU President/CEO Paul Marsh. “We want to make sure that what we are paying is very reasonable and is right for our members and right for the board members because they do give a large amount of their time. They have fiduciary responsibilities. They have liability. It is a big job and we want to make sure we are fair to all parties involved.”

Collectively, the Teachers CU board was paid $356,749 in 2011. One board member was paid $93,109, while two board members were paid $42,822 and $40, 914. The remaining eight board members were paid within the range of $8,491 to $33,645.

Marsh would not comment about compensation for individual board members but added that Mercer helped the credit union set its compensation philosophy and determined what is reasonable compensation for a financial institution with $2.3 billion in assets and serves more than 255,000 members.

Bert Hash, president/CEO of the $1.2 billion Municipal Employees Credit Union in Baltimore, said his credit union reviewed what other Maryland credit unions and credit unions in other states were paying board members to determine reasonable compensation for board members.

“Other banks pay their board members and we are in competition with them,” explained Hash. “If we want to attract board members who are accountable and responsible, they should be compensated.”

MECU's median board compensation is an annual stipend of $10,500. Total board compensation was $144,550 in 2011. Hash indicated the credit union's board compensation is reasonable when considering it's not nearly as much as what board members at competing banks are receiving in compensation.

But some executives disagree about what is reasonable compensation.

Richard Howdeshell, president/CEO of the $803 million Fort Worth Community Credit Union in Fort Worth, Texas, said paying board members too much may invite problems.

“If you compensate too highly you would attract an element that may not be in the best interest of the credit union,” he said. “I think those people serve on boards in large part for their own benefit, to get something back for their business or for themselves personally. It's been our experience that people who are motivated with the idea that they are helping their fellow credit union members tend to be better board members.”Fort Worth Community CU provides its nine board members with a $125 monthly stipend to pay for incidental expenses such as gas for attending meetings. In 2011, the credit union's total board compensation amounted to $12,544 with a median board compensation of $1,953.

“Not many would consider [$125] to be much of a benefit, to be honest,” said Howdeshell. “We don't compensate them for their time and expertise, but we  didn't feel it was appropriate to cost them money to serve on the board.”

didn't feel it was appropriate to cost them money to serve on the board.”

When asked what value their credit unions are getting in return for compensating board members, some CEOs struggled with providing specific examples.

“As a CEO, I can see the things the board contributes, and no, we don't document every comment that is made and every idea that they come up with and attribute it to an individual director,” said James Irving, president/CEO of the $370 million Greenwood Credit Union in Warwick, R.I. “As a CEO, it is an easier job to run the ship when you have people who understand what is going on.”

Greenwood CU paid its seven board members a total of $141,100, with annual stipends ranging from $10,000 to $33,200 and a median stipend of $22,400.

Next Page: Examples of Contributions

Some CEOs provided examples about how board members contributed to the growth of their credit unions.

Hash said the longtime leadership and strategic planning oversight of MECU Board Chair Herman Williams Jr. and Vice Chair Ernest Glinka, as well as other board members, were critical to the credit union's growth. Hash also said Williams provided him with valuable coaching and advice.

“MECU was at $350 million with 35,000 members when Herman took over as board chair 22 years ago,” he said. “Today, MECU has 105,000 members and $1.2 billion in assets.”

Hodges of Associated CU also said the guidance and coaching he received from a board member opened his eyes to the importance of political activism, advancing the credit union's interests and growth.

Nonetheless, other credit union executives are not sure whether paid directors tip the odds in their favor. “I don't know whether I can speak statistically on that,” said Root of Coventry CU. “But when I look at the Call Reports to see how our state-chartered credit unions are doing, there are a few that are losing money, the larger ones always make a ton of money and there are those that get a good return.”

Indeed, the financial performance of credit unions that do pay their board members compared to their peers, which includes the vast majority of credit unions that don't pay their board members, seems to be a mixed bag.

Data compiled from IRS 990 reports by Credit Union Times (see charts) show some credit unions that pay their board members have performed better than their peers, while a few have performed worse than peers and others have performed about the same as their peers.

For example, Rhode Island Credit Union paid its board members $224,675 in total stipends in 2011 and has posted a net income loss in four out of the past five years. In 2008, 2009, 2011 and 2012, the credit union had a total net loss of $3.1 million. What's more, at the end of the 2013's first quarter, the credit union lost $176,433, according to NCUA financial performance reports In 2010, the credit union recorded a net gain of $405,765.

Though Rhode Island CU has a strong net worth/total assets ratio of 11.40, higher than peer average of 10.54, its return on assets is negative 0.31, lower than the peer average of 0.62 last year. The credit union's loan growth was 7.34 in 2012, above peer average of 3.97, but it has been losing members. Rhode Island CU's membership has fallen by more than 2,400 from 27,089 in December 2008 to 24,674 in March of this year.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia's Trumark Financial Credit Union, which paid nine board members a total amount of $452,567 in 2011, has posted strong financial results, doubling its net income from $7.6 million in 2008 to $14.5 million in 2012, though in its peer group of credit unions with more than $1 billion in assets, the average net income was $26.2 million.

However, NCUA financial performance reports show Trumark's loan income has fallen from $45.4 million in 2008 to $40.7 million in 2012 but has more than doubled its fee income from $8.5 million in 2008 to $17.6 million in 2012.

The credit union also posted a net worth/total assets ratio of 10.32, only slightly below peer at 10.35, while its return on average assets was 1.05, versus peer average of 0.93 in 2012. Trumark's loan growth was 10.81, significantly above peer average of 6.24, but its membership growth was 1.48, below peer average of 3.87 last year.

The $2.7 billion State Employees Credit Union of Maryland in Linthicum, which paid a total of $216,462 to its 11 board members in 2011, has produced positive financial results as well.

Although it had a net loss of $16.5 million in 2008, it posted a net gain of $7.1 million in 2009 and more than doubled its income to $25.6 million by 2012, primarily by increasing fee income from $26 million in 2008 to more than $41 million in 2012.

The credit union's loan income has declined, however, from $89 million in 2008 to $86 million in 2012, and so has its investment income from $13 million to $7 million in the same years.

SECU's net worth/total assets ratio was 9.72, below the peer average of 10.35 in 2012, while its return on average assets was 1.07, above peer average of 0.93. The credit union's loan growth was 15.87, above peer average of 6.24 and its membership growth was 4.75, above peer average of 3.87 last year.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.