There are dumb ways and smart ways to steal from credit unions.

The dumb way is what most credit unions spend most of their time thinking about preventing, that is, the old-fashioned Bonnie and Clyde stick up, with guns a-waving, maybe a shot in the ceiling for punctuation.

The latest FBI bank crime statistical report – covering 2011 – shows there were 5,014 bank and credit union robberies. Loot was taken in 4,534 cases, meaning that in 11% of cases the perpetrator walked out the door empty handed.

Total amount taken was $38 million, of which $8 million was recovered.

Of the total cases, 398 were credit union robberies.

Clearance rates – arrests – vary by region but in New York City the most recently reported number is about 40%, meaning there is a four in 10 chance of going to jail, typically for several years. Cross country, bank robbery usually has one of the highest clearance rates, in part because of all the photographic evidence of the robbery.

Now for the big question: what's the take for the criminals? About $7,500 per heist. Granted, it's for a few minutes work but, typically, it will be split several ways – and remember the downside risk of spending a few years in a federal prison.

U.S. News & World Report quotes researchers, saying: “Robbing banks is no longer what you would call a crime of choice.”

That's because there are lots smarter ways to take money from financial institutions. They don't involve guns. And rarely result in jail time.

Here's a look:

Smile and Dial

If you got a call from the $21 million Allegheny Ludlum-Brackenridge FCU in Brackenridge, Pa., telling you your account had been compromised, please provide your PIN, so we can re-set — curse loudly and hang up. The polite may just want to hang up.

Literally dozens of financial institutions – often in small towns – suffer flurries of these dial-and- rob calling scams and, always, there are some dutiful citizens who precisely follow the instructions, “re-set” their accounts and watch their account balances vanish.

Literally dozens of financial institutions – often in small towns – suffer flurries of these dial-and- rob calling scams and, always, there are some dutiful citizens who precisely follow the instructions, “re-set” their accounts and watch their account balances vanish.

Criminals typically use automated robo-calling tools and a purchased telephone list. They put in no real effort, so they are not bothered by the wrong numbers and the connections to people who are not members of the target credit union.

Their computers just keep dialing and if only one in 100 numbers is pay dirt, it still is a rich return.

Arrest rates on these crimes are slim to none.

Next: Skim the ATM

It has been going on about as long as there have been ATMs but skimming remains a steady source of easy income for crooks with enough knowhow to acquire a skimmer, attach it to an ATM, and – usually – also install a tiny pinhole camera to get PINs.

Security blogger Brian Krebs shows how small – and undetectable – skimmers have gotten.

Even giant Navy Federal, the $52 billion Vienna, Va., fell victim when one of its ATMs in Germantown, Md., had a skimmer affixed, according to police reports.

Even giant Navy Federal, the $52 billion Vienna, Va., fell victim when one of its ATMs in Germantown, Md., had a skimmer affixed, according to police reports.

Across the country, in Camas, Wash., the $193 million Lacamas Credit Union also fell victim.

Every week, there are more skimmer cases that surface, usually with no arrest of the suspects.

The typical moment of vulnerability for the crook is retrieving the skimmer, the camera, and their data. Time that right – say, late on Sunday night – and arrest is highly unlikely.

The crime can be very lucrative. One crook in Milwaukee is said by police to have stolen around $3 million from 200 bank customers in a flurry of thefts.

The shift to PIN-and-chip EMV cards is supposed to put an end to skimming, but until 2015, skimmer crooks will have a clear path to profits.

Next: Identity Theft

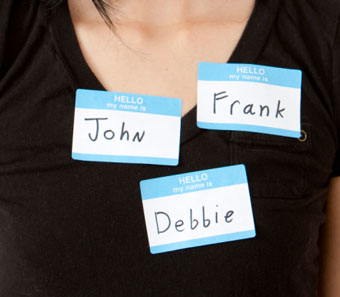

“Know Your Customer” may be a banking mantra but identity theft, associated with fraudulent loans, money laundering and more, is one of the nation's fastest-growing types of financial crime. It wins a high rank in the recent FTC round-up of complaint categories.

There is no obvious or easy cure for what is becoming an epidemic of stolen identities.

There is no obvious or easy cure for what is becoming an epidemic of stolen identities.

In a mobile world, it is easy to become someone else and it also is easy, in some cases, to persuade financial institutions that one is who one isn't.

This crime is one that at least occasionally ends in arrest of the perpetrator, as happened with a 26 year-old Armenian living in Southern California who recently was arrested in a massive identity theft fraud involving millions of dollars and at least one credit union victim, $666 million , Las Vegas-based One Nevada, according to police reports.

Next: Zeus Rules

Financial institution theft does not get bigger than Zeus, a long-running cybercrime that has looted hundreds of millions of dollars – possibly billions – from innumerable victims.

It works like this. A criminal buys a Zeus kit – at any of many cybercrime bazaars. Zeus is such a well-established tool that it is sold in what experts call a “malware as a service” arrangement. Tech troubleshooting and customer service come with the fee.

The criminal then seeks to inject his version of Zeus – which typically is customized to attack a particular financial institution – into victims' computers. The usual way is to rent a botnet of Zombie computers to do mass mailings of emails with infected links and/or infected attachments (bad PDF files are a current favorite).

When an infected computer visits a target site – say XYX Credit Union – the malware sends back to its controller the user's log in details (username, password) and then it is just a matter of timing the emptying of the victim's account.

A particularly brazen Trojan assault occurred in 2010 on the Treasury Federal Credit Union, where blogger Brian Krebs reported that the institution – which primarily serves Treasury Department employees in Utah – was looted of at least $100,000 due to infections of keylogging malware (probably Zeus or its close cousins).

Arrests are scarce. Criminals often are in distant countries where U.S. law enforcement has little reach. But even when criminals may be U.S.-based it simply is hard to persuasively link a particular cybercriminal with a particular crime.

Zeus may be the perfect banking crime, at least from the perspective of the criminal.

Last But Not Least: Get a Job in a Credit Union

ABC News had the story: the best way, tops, to loot a financial institution is to get a job in one. Bad bank examinations plus bad accounting plus bad compliance  equals a golden opportunity for crooks with sharp pencils, suggested ABC.

equals a golden opportunity for crooks with sharp pencils, suggested ABC.

The stories pile up:

* The only employee of H.B.E. Credit Union in Nebraska looted the tiny place of $635,000 over a span of at least five years. She now is in jail.

* Theresa Portillo, the sole employee of Women's Southwest FCU in Texas, stole some $3.4 million over an 11-year period.

* At United Catholic Credit Union in Temperance, Mich. the sole employee was convicted of stealing $2.1 million going back at least to 1985.

* At St. Paul Croatian FCU the CEO (and others) conspired, for many years, to steal many tens of millions from the institution, mainly via bad loans. He now is doing 14 years in federal prison.

You might say: the system works, they are all in jail.

But there are many small bank and credit union experts who wonder how many more crooked CEOs are out there. The stunning fact in every prosecuted case is how long the crime had gone on. Without getting detected.

Working inside a financial institution has to be the best – and certainly simplest – way to loot one.

Note: Neither Credit Union Times nor the author encourages theft from financial institutions. The story's purpose is trigger thinking about where best to allocate defensive resources.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.