During the first half of 2013, the NCUA approved 132 credit union mergers, up from 114 mergers approved as of June 30 last year, according to the NCUA's Insurance Report of Activity.

During the first half of 2013, the NCUA approved 132 credit union mergers, up from 114 mergers approved as of June 30 last year, according to the NCUA's Insurance Report of Activity.

If the pace continues, the number of mergers completed in 2013 could top 2012's total of 273 mergers, which was the highest number in six years. Not all NCUA-approved mergers convert into completed mergers, for a variety of reasons.

In 2006, there were 285 completed mergers, but after that peak the number had been declining until 2011. In 2007 mergers fell to 242 but then ticked up to 256 in 2008, according to NCUA's 2012 Annual Report. By the end of 2009, mergers dropped to 219 and bottomed out to 203 by 2010. The next year, however, the number increased slightly to 213.

John Worth, NCUA's chief economist, said the merger trend line since 2000 has held steady at about 60 consolidations every a quarter, or about 200 to 250 mergers a year on average.

Despite the slight increase over the last two years, experts are split over whether mergers will remain on the average trend line over the next few years or accelerate due to competitive pressures and an expected onslaught of new regulations.

“I believe one of the unintended consequences of compliance will double the rate of mergers by the end of this year or during next year,” said credit union attorney Michael Bell of the Royal Oak, Mich.-based firm Howard & Howard. “It's impossible to comply with regulations in an efficient way unless there are resources behind you.”

Worth, however, said it's too early to say whether regulations will drive mergers, pointing out that the majority of mergers occur because most small credit unions can only offer expanded services for members by merging into a larger credit union, a trend he said is expected to continue.

Bill Myers, who heads NCUA's office of Small Credit Union Initiatives, said regulators are well aware that compliance places a disproportionate burden on small enterprises. He said he expects small credit unions will be granted exemptions or the new regulations will be modified in some way so as not to increase costs.

“The increased complexity (of regulations) makes it tougher for credit unions, but (compliance) is not the main factor (for mergers) by a long, long, long shot,” he said.

While it may be uncertain whether regulations will force more small credit unions than ever to merge, one trend is for certain—the number of credit unions merging because of financial issues has significantly increased over the last five years, said David Bartoo of the Merger Solutions Group in Forest Grove, Ore.

For example, in 2008 more than 50 credit unions merged because they were financially troubled. In the previous three years—2007, 2006 and 2005—Bartoo said the number of financially distressed credit unions that merged averaged about 30.

Bartoo said credit unions that merged because of poor management, lack of growth, lack of sponsor or support and loss of membership—other categories listed in the NCUA report—were also financially distressed from declining earnings and diminishing net worth. He also said he believes some of the credit unions that merged to offer expanded services were also facing mounting financial challenges and pressures.

Among the credit unions that merged in 2008, the NCUA labeled 51 of them in poor financial condition, but an additional 60 credit unions merged because of either poor management, lack of growth, lack of sponsor/support or loss of membership. In 2009, 49 credit unions had to merge because they were in poor financial condition, and an additional 43 credit unions were forced to merge because of poor management, lack of growth, loss of membership or sponsor.

In 2010, the numbers were 55 and 23, in 2011, 34 and 42 and in 2012, 52 and 43.

And, the trend appears to be continuing this year.

Although the NCUA report listed 28 credit unions that merged in the first half of 2013 because they were in poor financial condition, an additional 13 merged because of poor management, lack of growth, loss of membership or lack of sponsor or support.

Some credit unions, particularly small ones, weren't quick to recover from the Great Recession and the subsequent slow economic recovery due to low loan-to-share ratios, Myers said.

“They had relied on investment margins to maintain them, and those margins are just not available now,” he said. “So you have some stress on their income statement because of that, and of course, that leads to mergers.”

Since 2000, 75% of merged credit unions had assets of less than $10 million, and another 22.5% had assets from $10 million to $100 million. Meyers said in February that credit unions with less than $30 million have a very difficult time establishing a fully functioning, sustainable business.

Randie Dial, a partner with Indianapolis, Ind.-based consulting firm CliftonLarsonAllen, said he has seen an increase in mergers among larger credit unions, too.

Dial said he has received several inquiries from credit unions with assets of about $300 million that are discussing the possibility of merging with credit unions of similar asset size, commonly referred to as a merger of equals.

“The larger ones are looking for mergers to become stronger and more stable,” he said. “If they can find enough cost synergies going forward, they can be stronger as one instead of competing head to head, so a merger can make a lot sense.”

But Kevin Kirksey, a valuation and risk analytics manager for ALM First Financial Advisors in Dallas, doesn't see a merger of equals trend taking shape.

Next Page: Across the Map

“With our experience, we have seen the transaction data suggest that there is still reluctance for merger of equals,” he said. “It's challenging for credit union executives to integrate their business into another credit union. A merger is about integrating cultures as well. It's not just about assets, liabilities and earnings.”

“With our experience, we have seen the transaction data suggest that there is still reluctance for merger of equals,” he said. “It's challenging for credit union executives to integrate their business into another credit union. A merger is about integrating cultures as well. It's not just about assets, liabilities and earnings.”

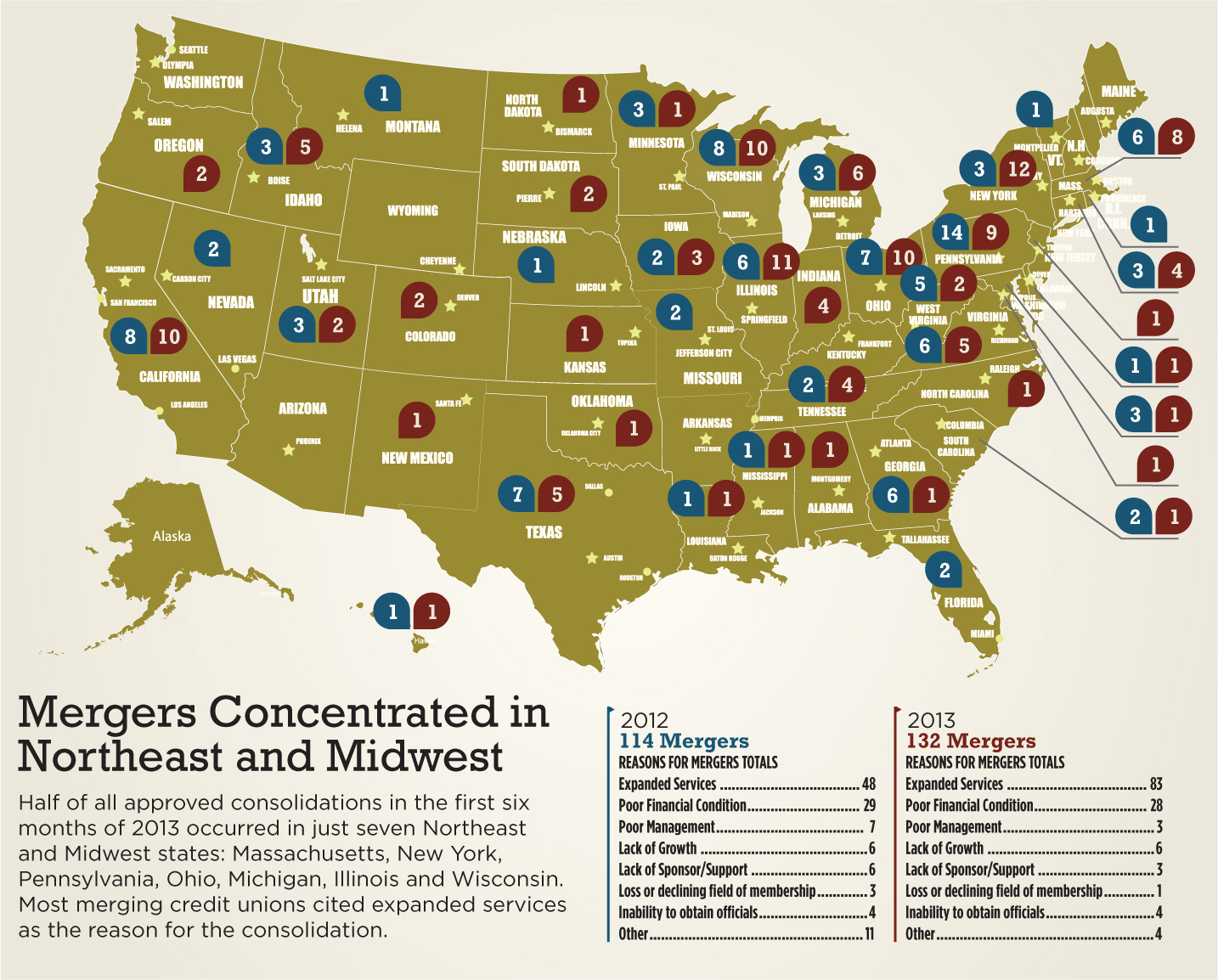

An interesting trend that surfaced from NCUA's merger reports is that 66 mergers, or 50% of approved consolidations in the first six months of 2013, occurred in just seven Northeast and Midwest states including Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin.

(Click on the map at right to see expanded version.)

New York posted 12 mergers, the highest in the country, while Illinois was second with 11, and Ohio and Wisconsin tied for third with 10 mergers each. Pennsylvania and Massachusetts followed with nine and eight mergers, respectively.

Likewise, during the first half of the year in 2012, nearly half of the 114 approved mergers occurred in nine Northeast and Midwest states including Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and Wisconsin, as well as New York, Connecticut, Michigan and Minnesota.

NCUA's Worth said the geographic trend likely occurred because credit unions in those states are often SEG-based, associated with manufacturing plants, labor unions or businesses. Those manufacturing industries have been shrinking in the number of employees because of downsizing, plant closings or relocations to southern states or other nations.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to CUTimes.com, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited CUTimes.com content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking credit union news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Shared Accounts podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical coverage of the commercial real estate and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, GlobeSt.com and ThinkAdvisor.com

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.